Metacognition at Hillside Primary School

At Hillside, our staff have a secure understanding of how children learn best and we are determined as a school to develop children’s self-awareness skills. Ensuring that our children leave Hillside with a secure understanding of how they learn and can call upon a bank of strategies to support them is integral to us. Research carried out by The Educational Endowment Foundation’s (EEF) on Metacognition underpins our thinking in school. Metacognition is defined as not simply “thinking about thinking”, it is much more complex than this. Metacognition is actively monitoring one’s own learning and, based on this monitoring, making changes to one’s own learning behaviours and strategies. Although a metacognitive approach typically focuses on allowing the learner rather than the teacher to take control of their own learning, this is not to say that our teachers have no role to play. Indeed, our teachers and staff are fundamental to the development of younger pupils’ metacognitive skills. For our pupils to become metacognitive, self-regulated learners, we must:

At Hillside, our staff have a secure understanding of how children learn best and we are determined as a school to develop children’s self-awareness skills. Ensuring that our children leave Hillside with a secure understanding of how they learn and can call upon a bank of strategies to support them is integral to us. Research carried out by The Educational Endowment Foundation’s (EEF) on Metacognition underpins our thinking in school. Metacognition is defined as not simply “thinking about thinking”, it is much more complex than this. Metacognition is actively monitoring one’s own learning and, based on this monitoring, making changes to one’s own learning behaviours and strategies. Although a metacognitive approach typically focuses on allowing the learner rather than the teacher to take control of their own learning, this is not to say that our teachers have no role to play. Indeed, our teachers and staff are fundamental to the development of younger pupils’ metacognitive skills. For our pupils to become metacognitive, self-regulated learners, we must:

- Set clear learning objectives.

- Demonstrate and monitor pupils’ metacognitive strategies.

- Continually prompt and encourage our pupils along the way.

Metacognitive skills are developed from an early age, as early as EYFS, and children are encouraged to plan, monitor, evaluate and make changes to their own learning behaviours.

Metacognitive knowledge refers to what pupils know about learning. This includes:

- The pupil’s knowledge of their own cognitive abilities (e.g. “I have trouble remembering my eight times tables”).

- The pupil’s knowledge of particular tasks (e.g. “the spelling of some “-tion” words is difficult”).

- The pupil’s knowledge of the different strategies that are available to them and when they are appropriate to the task (e.g. “If I create a timeline first, it will help me to understand what happened during the First World War”).

Research demonstrates that metacognition must be explicitly taught; at Hillside, we recognise they are not innate skills – and our children need lots of support from the teacher if they are to develop these skills. Our teachers have made children aware of what metacognition is and model the skills explicitly so that children can learn from the masters. We model being metacognitive through the context of the lesson rather than stand-alone teaching as research supports this approach.

Research demonstrates that metacognition must be explicitly taught; at Hillside, we recognise they are not innate skills – and our children need lots of support from the teacher if they are to develop these skills. Our teachers have made children aware of what metacognition is and model the skills explicitly so that children can learn from the masters. We model being metacognitive through the context of the lesson rather than stand-alone teaching as research supports this approach.

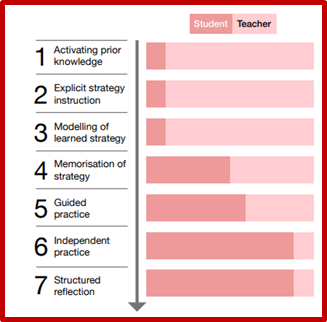

We use a seven step guide when teaching metacognition in school:

- Activating prior knowledge – the teacher discusses with pupils the different causes that led to the First World War while making

notes on the whiteboard.

notes on the whiteboard. - Explicit strategy instruction – the teacher explains how a “fishbone” diagram will help organise their ideas, with the emphasis on the cognitive strategy of using a “cause and effect model” in history that will help them to organise and plan a better-written response.

- Modelling of learned strategy – the teacher uses the initial notes on the causes of the war to model one part of the fishbone diagram.

- Memorisation of learned strategy – the teacher tests if pupils have understood and memorised the key aspects of the fishbone strategy, and its main purpose, through questions and discussion.

- Guided practice – the teacher models one further fishbone cause with the whole group, with pupils verbally contributing their ideas.

- Independent practice follows whereby pupils complete their own fishbone diagram analysis.

- In structured reflection the teacher encourages pupils to reflect on how appropriate the model was, how successfully they applied it,and how they might use it in the future.

We believe there are two crucial strategies to use in the classroom that are conducive to effective metacognition:

1, Effective use of teacher modelling

Our teachers make explicit what they do implicitly and make visible the expertise that is often invisible to the novice learner. The best modelling involves the teacher thinking aloud.

For example, a teacher may write a short paragraph of persuasive text to model how to use rhetorical devices. As she/he is writing, they explain every decision they are taking, and articulate the drafting and redrafting process that is essential.

2, Providing appropriate levels of challenge

We believe if pupils are not given challenging work to do – if they do not face difficulty, struggle with it and overcome it – they will not develop new and useful strategies, they will not be afforded the opportunity to learn from their mistakes, and they will not be able to reflect sufficiently on the content with which they are engaging.

We believe if pupils are not given challenging work to do – if they do not face difficulty, struggle with it and overcome it – they will not develop new and useful strategies, they will not be afforded the opportunity to learn from their mistakes, and they will not be able to reflect sufficiently on the content with which they are engaging.

As well as challenging their thinking, our pupils need to think efficiently if they are to cheat the limitations of working memory. And while pupils must be challenged and must struggle with new concepts to transfer them to their long-term memory,, if the work is too hard, they are likely to hit cognitive overload. Cognitive overload is where children try to hold too much information in working memory at one time and thinking fails. Therefore, teachers endeavour to plan work that is beyond pupils’ current capability but within their reach. We want children to struggle but must also to be able to overcome the challenge with time, effort and support.